HAL seems to have finally realized that it needs to be a final integrator after all! Or has it?

(http://m.thehindu.com/news/national/hal-seeks-to-lighten-light-combat-aircraft-burden/article7617119.ece) It now wants to offload major parts of the airframe to the large private players. We can now see the ‘biggies’ trooping to HAL to have a bite of the various platforms that HAL has been struggling to deliver to its reluctant customers.

How sincere is HAL when it makes such statements? I say this because this same intent has been repeated over the years ad nauseum without any action on the ground:

2002: www.thehindu.com/thehindu/2002/06/13/…/2002061301830400.htm

2003: www.thehindubusinessline.com/2003/02/12/…/2003021201020200.htm

2005 October: www.thehindubusinessline.com/…/hal…outsourcing/article2193883.ece

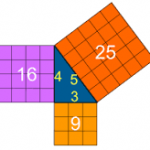

If anybody thinks that this would make an impact on the Indian military aerospace sector, they are going to be sadly disappointed once again. All that this would achieve is to allow the large private players to put in place a certified system of producing airworthy structures, besides churning out riveted airframes and that too out of jigs and fixtures to be transferred to them by HAL. What nobody seems to notice is that a large part of a flying platform comprises its accessories and systems, including the most important power plant (engine), that really determines the flying as well as fighting capability of that aircraft. Onboard systems constitute about 25% of the acquisition cost of a military aircraft and along with the power plant, they account for 50% of the total cost. These also need maintenance and upgrades over the long operating lifecycle of at least 35 years. Considering that such systems can be tailored and modified to suit multiple aircraft, this constitutes the core of the aerospace industry. So, isn’t it silly that we are still talking only of manufacturing the shell and nothing about indigenous development and manufacture of all airborne systems such as avionics, electrical, hydraulics, pneumatics, air-conditioning and pressurization, cockpit instruments, weapons control, etc?

The Lucknow division of HAL was established out of the need for self-reliance in the development of accessories and systems. It has miserably failed to meet its mandate and hence this is where a multi-billion dollar opportunity exists for a large number of MSMEs alone. They can do wonders if pool their knowledge base, collaborate and synergize with each other and HAL can benefit by this too. This could lead to the creation of multiple consortia across the country each of which could be a potential exporter over time.

It is interesting that the CMD, HAL has talked of hand-holding. Let us look at their past track record. Five years ago, two divisions of HAL (Nasik and Lucknow) cancelled their outsourced manufacturing orders to a small private company stating that the labour unions had objected to outsourcing of work to the private sector. This was after going through a whole process of tendering, L1, price negotiation, and release of formal Purchase Orders. Is the CMD of HAL now sure that this will not happen again? Or, would the divisions now go to the unions to plead with them?

Talking of the 2600 SMEs that are supposed to be supplying parts to HAL, has anybody wondered what quantum of business each of these SMEs derive from HAL? If they are only manufacturing bolts and nuts, they could certainly graduate to aggregators by putting them together into a bracket or sub-assembly. That’s not what the SMEs would like to aim at. This precisely has been the problem with HAL. They never seem to be able to recognize the huge potential that lies untapped among the many competent and highly capable MSMEs of this country. Had HAL encouraged and facilitated the formation of clusters of MSMEs two decades ago, these would by now have graduated to system integrators, with each cluster delivering a communication or navigation or hydraulic system.

Why has HAL done nothing to support and encourage the existing MSMEs, many of whom are CEMILAC certified, who have already demonstrated their capabilities by manufacturing complete airborne equipment? Why does HAL not realise that creating such an ecosystem would be a force multiplier?