Part 4 – contd from Part 3:

There is a misplaced belief that Indian companies do not invest in R&D. The terms ‘Research & Development’ or ‘Design & Development’ are often misunderstood and used inappropriately. In the context of indigenisation efforts of the private sector, especially MSMEs, ‘Design & Engineering’ should be the more appropriate term. It is a well accepted fact that Indian MSMEs are highly innovative, enterprising and come up with unique solutions to various problems. Innovative ideas could range from a simple tweaking of a design or reverse engineering of a foreign OEM product. All these activities involve considerable D&E focused on the specific product. The only problem is that private industries do not have the habit of monitoring and accounting such expenditure under a separate head called ‘R&D’. This is due to the fear of the tax-man not allowing these costs as expenditures and treating them as capital investment (which it certainly is) and should result in repetitive long term returns over a period of at least 5 years. In the case of MSMEs indigenising complete LRUs or sub-systems, there is certainly a high indigenous D&D content whose risk is justified only if there is a likelihood of repetitive bulk production orders. The expected Return on Investment (ROI) has to be linked to the risks of D&D. ROI is also linked to the quantum of sales of the product over its lifecycle. Hence, the economic viability of indigenisation has to be based on future bulk production orders from the Armed Services. This is where a serious flaw exists in the indigenisation programmes of all Armed Services and DPSUs. They either do not know what their future requirements are or do not wish to reveal it. In either case, it is almost impossible for a private industry to assess whether there is any worthwhile business potential.

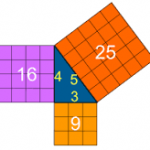

Yet another misconception among the Armed Services is that they have reimbursed the D&D costs to the Vendor at the end of successful completion and hence the vendor is fully compensated. They do not seem to appreciate that D&D cost is very different from the lifecycle value of the product realized. Total value realized from consumer and industrial products over their lifecycle would be more than 100 times their D&D cost. In the case of the specialized A&D sector,  it should be even higher due to the high value addition of the products. Hence, choking a vendor by not providing him serial bulk orders at least for a few years would amount to killing him without sustainability. This leads to a ‘lose-lose’ situation with both the successful vendor gradually dropping out of business and the Services losing a successful vendor, who could have multiplied his initial success into many more successful projects and graduating to higher levels of technology.

it should be even higher due to the high value addition of the products. Hence, choking a vendor by not providing him serial bulk orders at least for a few years would amount to killing him without sustainability. This leads to a ‘lose-lose’ situation with both the successful vendor gradually dropping out of business and the Services losing a successful vendor, who could have multiplied his initial success into many more successful projects and graduating to higher levels of technology.

Profit was considered a dirty word in our country till recently. While it has turned decent, it still retains a gray shade among the Armed Services and DPSUs. How much or profit is ‘decent’ and how much is to be considered ‘profiteering’? Any B-school would teach that profit is all about maximization at every opportunity. Even in the background of a patriotic national sense connected with indigenisation of weapons and systems, profits allow the industries to grow and diversify multi-dimensionally. Ultimately, this becomes a national asset since the industry in involved in achieving self-reliance of defense equipment. In the absence of profits realized through repetitive sales, the industry would turn unsustainable. This appears to be the present state of MSMEs engaged in defense indigenisation. Only those who have an alternative revenue stream in a different domain are able to sustain their business even though the A&D sector is a drain on the other stream.